|

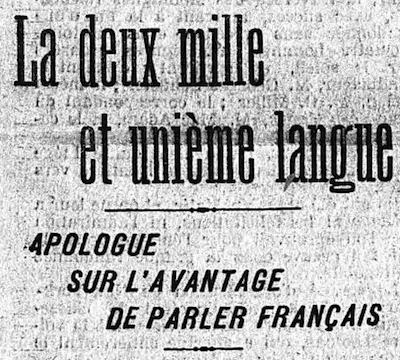

| "The two-thousand-and-first language" in their view, one too many. |

Other reading I’ve done has shown that Le Matin was fairly hostile to the Esperanto movement, in part perhaps to the appeal Esperanto had for the labor movement in Europe. The conservative newspaper does not seem to have been a fan of organized labor in any language, although the motive behind the Le Matin piece was the fear that Esperanto would reduce the prestige of French. If you want to be a truly sophisticated world traveller, you should speak French. Ask any Frenchman.

Here’s what the Sun wrote:

The Paris Matin recounts the sad story of a deceived Esperantist. The person in question was a young Levantine[1] named Radomir, who sailed to France with the hope of polishing up his newly acquired tongue—as one would visit Paris to hear at the theaters the best French. Numerous journals printed in Esperanto had informed the green young fellow with the exotic and Sardou-like[2] name that all the world spoke Esperanto nowadays. Whether at church or bank, theater or café, in the street or on the housetops, there was one sure method of communication with one’s fellow man, Esperanto. Neglecting the memorizing of a single word of French, Radomir declares at the beginning of his sea trip his troubles began. No one understood Esperanto, not even the waiters. Occasionally a word that sounded like French or Italian would be picked out, but it did not carry him very far. Employing that most ancient of all languages, that of the gesture, the traveller managed to reach Paris. There the word hotel, the same in many tongues, brought Radomir a roof over his head. Again he was disappointed. No Esperanto on the bill of fare. He called a man “sinjor”[3]—for monsieur—and was laughed at; but the crowning insult came after he had addressed a young woman in polite Esperanto as “sinjorina,”[4] for she promptly boxed his ears. The phrase sounded too much like singe—monkey. He had mispronounced it. Howerver, after a few weeks in the agreeable capital Radomir deputed consoled; for, as he put it, he had brought to Paris much Esperanto, and at least took away a little French. The French, he added, is the true key that unlocks all tongues, no matter in what country; while the pretensions of the Esperantists with their propaganda, their congress and their unfounded boasts of the machine made speech’s popularity had led him astray. He returned to his home a wiser young man, but shorn of his faith in Esperanto.Deceived. Oh, those evil Esperantists, fooling people into thinking the Esperanto would be useful. I decided to hunt the original to see what it said. The Le Matin piece was published on July 31, 1908.[5] In the French original he seems to actually be from Annapolis, and not the Middle East.

Bien qu’il vécût fort heureux dans la petite ville d’Annapoli, où son père était un riche marchand d’essence des rosesIt kinda wrecks it for the Sun if Le Matin is making fun of an unsophisticated American. Also in the original, his friends are a bit jealous, and so convince him that Esperanto is the only way to go. So he reads some French literature, Molière’s The Miser, although in a Esperanto translation. The claim that sinjorino sounds like singe is an invention of the Sun, though in the original Radomir complains that Esperanto uses the word viol (actually “violo”) to mean “violet.” The French word viol means “rape.” So a nice Esperanto word sounds like a nasty French one. Get over it.

Though he lived happily in the small town of Annapolis, where his father was a wealthy merchant of rose oil.

It wasn’t just any Frenchman behind this. In Le Matin, it’s a signed piece, so we find out who is behind this tale: Remy de Gourmont, the French poet. It is almost certainly a work of fiction. There was no Radomir. De Gourmont ends his piece saying to Radomir that the French consider Esperantists to be “inoffensive maniacs,” to which Radomir replies,

— Des méchants et des ignorants, monsieur, des méchants, des méchants…Despite that the piece is a slam on Esperanto, the Le Matin piece starts off by saying that Esperantists won’t complain, because it still draws attention to their attempt to create an international language. Both the French and English versions make the claim that the problem with Esperanto is that no one speaks it, and they both make the claim that French works so much better as an international language. But I would suspect that if someone walked into the offices of the Sun in 1908 speaking only French, no one would be able to help them.

Wicked and ignorant people, sir, wicked people, wicked people…

What de Gourmont is claiming, however, is that there is a network effect that persists far beyond the borders of Paris and even France, that enough people speak French—even outside of France—that the language is worth learning if it isn’t your native tongue. Currently, native English speakers get to take advantage of this network in which the language of international tourism is English. Radomir would have found his English useful in 2014 Paris, even if it might not have been in 1908.

Few people speak Esperanto, so there is not a compelling reason to learn Esperanto. If lots of people spoke Esperanto…

Some years ago, we stopped in Luxembourg. At the café where we ate lunch, I realized that our waiter—who spoke English to us—was speaking French to one adjacent table, and German to another. He said he spoke those languages, Lexemburgish, and Finnish (because for some reason Luxembourg was popular with tourists from Finland). I suppose if there had been a stream of Esperanto-speaking customers, he might have known that too.

French is not currently terribly useful in places like New York, London, Berlin, or Madrid. (Nor is Esperanto.) And despite what M. de Goncourt said, Esperantists are not (generally) wicked and ignorant people.

- The Eastern Mediterranean region of the Middle East. ↩

- French playwright. The word “fedora” comes from the name of one of his characters. ↩

- Sinjoro, actually, though it’s taken from the same root as monsieur. ↩

- Sinjorino. Sinjorina would be an adjective with a meaning roughly of “pertaining to married women.” Gourmont got it right. ↩

- The French National Library has Le Matin as a searchable resource, however, I’m not in any need of any other old newspapers to read. ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment